Mast cell tumours originate from Mast Cells

Mast cells are found in normal healthy dogs; they are white blood cells, found near blood vessels within the connective tissue. The cells are particularly equipped to catch germs and prevent them from spreading throughout the body, but they are also able to repair tissue and assist in creating new blood vessels. Essentially, they are pretty important as they play a key role in defending the body and keeping the immune system healthy and strong. They also release histamine and other compounds which are involved in allergic reactions.

So, a mast cell tumour is…?

Mast cell tumours occur when cancerous changes occur in the mast cells, allowing them to multiply too quickly and out of control. Mast Cell Tumours are very variable in appearance, from smooth, skin coloured swellings to angry looking masses with numerous, bumpy lumps. The lump may well appear inflamed and be itchy, causing your pet some irritation and discomfort. If the tumour is in a more progressive stage then vomiting and diarrhoea can occur due to the excess levels of histamine produced by the cells of the tumour.

Brachycephalic breeds (the ones with short snouts and wide heads e.g. Boxers, Pugs, Bulldogs etc.) are at a particularly high risk of developing these tumours. The perineum (the area between the genitals and anus) is a common site for mast cell tumours, but they can also occur on the limbs, face or anywhere on the body. If you notice a new lump anywhere on your pet, it is always worth getting it looked at by one of our vets.

Sometimes the tumour will grow quickly so it is important to contact us ASAP to discuss any new lumps appearing on your pet. Histamine, released by Mast Cell Tumours, can cause swelling in the surrounding skin, and can cause them to fluctuate in size – they can even reduce in size after a rapid increase, so even if a lump appears to be getting smaller it is vital to get it checked.

Grading

There are different grade categories that a mast cell tumour can fall into; please use the overview below for a whistle-stop description of each level. If your pet does have a mast tumour, you will be told which grade their lump falls under.

Grade 1:

A slow growing, benign lump.

Grade 2:

The tumour has spread to deeper, subcutaneous layers. Fast growing and unpredictable growth. Likely to be malignant.

Grade 3:

Deep, aggressive tumours. Grow quickly. Malignant.

Grade 4:

The tumour has already spread or metastasised, to another part of the body.

Diagnosis

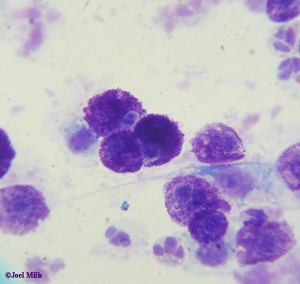

It is not impossible to diagnose a mast cell tumour simply by looking or examining the lump. Mast Cell Tumours are usually diagnosed from cells gathered by ‘Fine Needle Aspirate’, our vets use a need to sample the mass. We may need to do a variety of other investigations such as X-ray, ultrasound, blood tests and lymph node and bone marrow sampling to establish if the tumour has spread.

Treatment

Surgery is the usual method of removing mast cell tumours, where surgery is difficult or impossible due to the location of the tumour radiotherapy may be used. Depending on the grade of the tumour, a wider circumference of skin may need to be removed to prevent the tumour spreading. The surgery varies enormously depending on the location of the tumour and its size, our vet team will inform you fully of the procedure and aftercare. If the Mast Cell Tumour is in a position where surgery is difficult or impossible radiotherapy may be used to remove the tumour.

If the mast cell tumour has spread, a course of chemotherapy may be required after the operation. The chemotherapy will target any remaining dangerous cells that have not been removed by surgery or radiotherapy.

Mast cell tumours can be dangerous for your dog but the sooner you get your dog checked, the sooner a diagnosis can be made and the better the chances of successful treatment.

Regular body checks of your pet are a great way of knowing your animal’s body and the best way to pick up on something out of the ordinary.