So, your bitch has met with the stud dog – hooray! But what happens next? What do you have to do? Is there anything to watch out for? No need to worry – read on for all the answers you need!

How long is her pregnancy?

The average pregnancy is 63 days from the first mating; however, the bitch’s season is quite long, sperm can survive inside for quite a while, and so there is always some natural variability. We certainly wouldn’t expect her to produce any puppies before 56 days, and if she’s reached 73 without anything, that suggests a problem with the dates, or uterine inertia.

How do I know if she’s pregnant?

Diagnosing pregnancy in the bitch is not as easy as in humans. This is mainly because the bitch’s body prepares for pregnancy after every season, whether or not there are actually any pups present. So, a progesterone test (for example) is essentially useless – the bitch thinks she’s pregnant anyway, every single time! There is one slightly dubious and two reliable and widely available methods we can use to determine pregnancy:

Palpation – an experienced vet can sometimes feel the puppies between 25 and 30 days after conception – however, a fat, tense or anxious, or large breed bitch can make this really difficult. As a result, you can get false negatives, and occasionally even false positives. We do not, therefore, recommend it!

Relaxin Blood Test – although progesterone tests are useless, there are other hormones in pregnancy! The Relaxin test is reliable and accurate, and can be used from 25-30 days post conception.

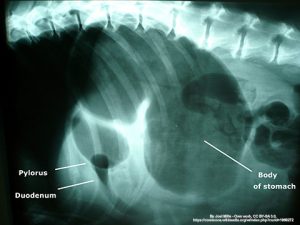

Ultrasound Scan – this is the most common and most reliable method. It is first reliable at 25-30 days and at this time the heartbeats can usually be seen quite clearly. In the hands of an experienced vet, sometimes it’s possible to say that she is in pup from three weeks, but it’s impossible to say with certainty that she isn’t at this age. Ultrasound scans also allow us to measure the size of the puppies, and work out how old they are. This can help us narrow down the due date if a bitch was mated several times! However, the ultrasound scan can only give you a rough idea of the numbers – an accurate count of foetuses is not possible.

Are there any health precautions I need to take?

You want the puppies to be as healthy as possible, so making sure she has a good diet and suitable preventative care are really important.

Diet – a suitable fully balanced diet is ideal; we’d generally recommend against a raw food diet in pregnancy as it’s very hard to get the nutrient levels right. We also STRONGLY advise against giving any calcium supplementation – doing so, ironically, increases the risk of eclampsia (see in Part 2). In terms of volume, she doesn’t really need any more calories until the last 2 weeks or so and, if you overfeed, there’s a risk that she’ll be too fat, or the pups will be too big, for her to give birth normally. Of course, after birth, she needs more or less as much as she can get to make milk for her puppies!

Vaccination – puppies are protected for the first 4-6 weeks of life by their mother’s immune system, so it’s important that she is fully up to date with vaccinations, ideally before she gets pregnant. If her vaccination status will lapse during her pregnancy, you can give her a booster, but it’s probably better to boost her 3-4 weeks before she goes to the dog. If Canine Herpes (a nasty infection that is usually fatal to puppies) is a problem, there is a short-acting vaccine given in pregnancy that will protect them – but we don’t think it’s usually necessary.

Worming – some nasty roundworms can invade a puppy through the placenta, and also through the milk. During pregnancy, dormant worms may wake up and become active, so worming with a puppy-safe wormer during pregnancy is vitally important. Talk to us for advice on the dosage because it’s a bit different from normal 3-monthly doses!

How should I prepare as she gets near her time?

In the last couple of weeks of pregnancy, introduce her to the area where you want her to whelp. Remember, she’ll only whelp down somewhere she feels comfortable, safe and secure! Ideally, a box she can hide away in, with comfortable bedding (towels are good – they’re going to get messy! – and newspaper underneath is a must), nice and warm and free from draughts.

In Part 2, we’ll look at the whelping process itself.

If you’ve got any other questions, feel free to call us for advice. If you think something’s going wrong, call us any time, 24/7, and talk to one of our vets.