A GDV is one of the most serious emergencies that any dog a can suffer. The survival rates if not rapidly diagnosed and treated are really low, but rapid emergency surgery can genuinely save lives.

What is a GDV?

GDV stands for Gastric Dilation and Volvulus. It occurs when the stomach fills with gas (Dilation or Bloat) and then twists on itself (Volvulus or Torsion). As it twists, it traps the gas inside; this also blocks the blood vessels returning blood to the heart, meaning that dogs with a GDV rapidly go into shock. As the body is starved of oxygen (due to the shock state), tissues start to die, releasing potassium into the blood vessels. This can slow and stop the heart. This is a real, top-priority emergency as affected dogs can die within an hour or so of first showing symptoms.

What causes it?

The exact cause isn’t known for certain, but we do know that deep-chested dogs (e.g. Setters or Great Danes) are at increased risk; there also seems to be a genetic component as animals who have a litter-mate who suffers a GDV are more likely to develop one themselves. In addition, exercising vigorously immediately after eating also seems to be a risk factor.

What are the symptoms?

In most cases, the dog initially appears restless or uncomfortable; then they begin to retch. This is usually without actually producing anything, although in some cases some frothy foam may appear. This is a “red-flag” danger sign! Soon afterwards, you may notice the abdomen (tummy) beginning to expand and bloat, and they will then rapidly show signs of shock with pale gums, weakness, fast heart rate, and collapse. Once the dog is has reached this stage, the prognosis is poor, and many dogs actually die on their way into the clinic.

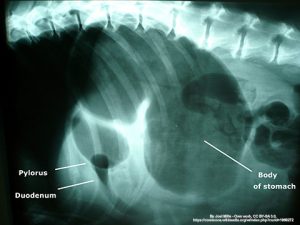

How do your vets diagnose it?

The symptoms are usually pretty clear, however, an X-ray will confirm the diagnosis if necessary.

How can it be treated?

The immediate first aid that our veterinary team will perform is to try and pass a stomach tube and let the gas out of the stomach. This won’t fix the problem but will buy ten to twenty minutes to get them stable enough for surgery. If the dog is in severe distress, but it isn’t possible to pass a tube past the twist in the stomach, the vet may be able to use a needle to release the gas.

The biggest problem with this condition is how unstable these dogs are – most GDV dogs are so sick on arrival that anaesthesia for surgery could easily be fatal. It’s necessary to treat the shock (with massive doses of intravenous fluids) and bring their blood potassium down into the safe range (usually with fluids, although sometimes medications may be used as well) before they can be operated on. Once they are in a better physiological state, we’ll rush them into theatre, and the vet will open the abdomen and decompress the stomach. If any part of the stomach has been starved of blood for too long and has died, we’ll remove these sections. Likewise, it is sometimes necessary to remove the dog’s spleen if it has become twisted as well.

The next phase is to fix the stomach to the abdominal wall so it cannot twist again in the future – this is called a gastropexy. In fact, if you have a very high-risk dog, we can perform this as an optional (non-emergency) treatment, typically at the same time as neutering, to prevent them developing a GDV in the future.

A dog who has had GDV surgery will usually need a while as an inpatient in intensive care to recover; however, if they make it through surgery, the prognosis is usually fairly good.

What’s the prognosis?

According to the latest research, about 60% of dogs with a GDV will die. However, if they are stable enough to be operated on, the majority of these (80%) will survive. The take-home message is that the earlier they’re seen by our vets, the more likely it is that they’ll come home – so don’t delay!

If you think your dog MIGHT be showing signs of a GDV, call us IMMEDIATELY!